Get the latest news, inspiring stories, upcoming events, and valuable support services delivered straight to your inbox.

ALL NEWS

Filter by type

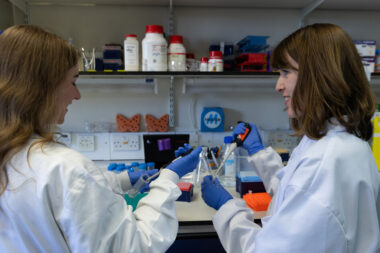

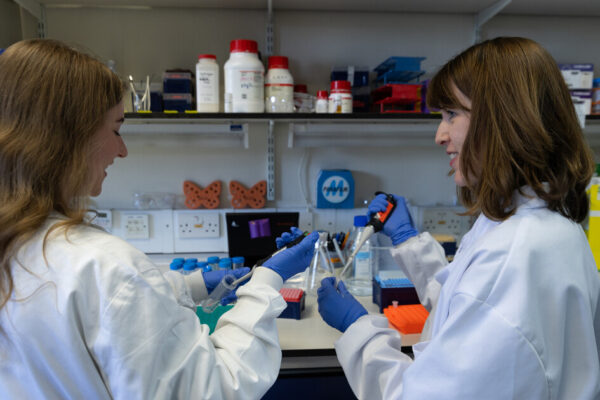

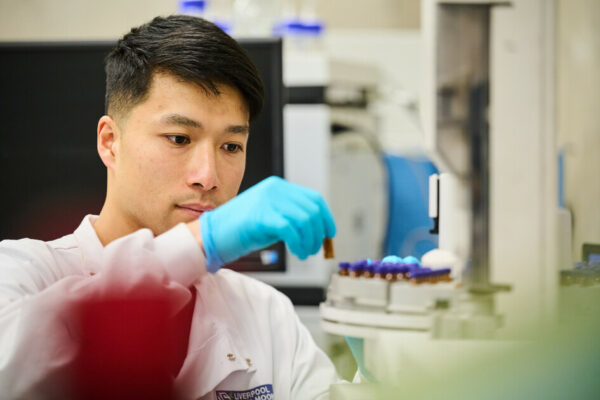

Our research investment keeps growing

September 12, 2025

SMA to be added to newborn screening programme in Scotland from Spring 2026

September 8, 2025

Study begins to uncover how exercise affects muscles in FSHD

August 22, 2025

Givinostat: more evidence needed before a decision on NHS access in England

August 11, 2025

How gene editing could transform muscle repair

July 25, 2025

Our £1 million investment to transform clinical trials for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

July 15, 2025

Our work with partners to speed up the introduction of newborn screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

July 9, 2025

How we’re supporting the future of research into muscle wasting conditions

July 4, 2025

Second treatment for myasthenia gravis not approved for NHS use in England

June 26, 2025

New FSHD treatment shows early promise in clinical trial

June 16, 2025

Our Young Ambassador Carmela makes history as youngest ever MBE

June 13, 2025

“It’s a fitting legacy for my son”: Our Patron Ian Corner recognised in King’s Birthday Honours List

June 13, 2025